Tendency Films Pt. 2: 1925 - 1929

(2/3) - Further Developments

In 1927, Ito made Servant (下郎), "a savage exposure of Tokugawa-period feudalism," which some scholars consider to be "a direct forerunner of the tendency film" (Anderson, 65). Soon after, he began the 4-hour, 3 film series A Diary of Chuji's Travels (忠次旅日記). The series focuses on Chuji, a kindly yakuza boss (known then as a bakuto, or gambler), and his interactions with various people, among others a certain geisha. In saving the geisha from a life of indentured work, Chuji commits an act of "rebellion against the rigid social structure of Edo Japan" (Filmlinc). After many travels, he is finally captured by the police at the end of the film. Several elements of the narrative, particularly the depiction of a nihilistic criminal as kind and heroic and the authorities as cruel and heartless, represent the anti-establishment, if not anarchist, overtones frequently appearing in Ito's films. In these years, as Anderson and Richie write, his "philosophy of rebellion and his exaltation of the nihilistic hero" began to have an increasingly forceful presence. These films were very popular, largely because "Ito's philosophy was, in part, the philosophy of his time" (65).

A Diary of Chuji's Travels Pts. 2 & 3 (1927) -- the only extant segments

Tension Grows

The trends of agitation and social strain beginning after the earthquake only quickened in the last few years of the decade, and the period-tendency film format continued to be developed and refined. The passing of the Peace Preservation Law made it increasingly dangerous to produce films with themes and characters that may have been viewed as oppositional to the government's policies. As the 1920s neared their end, left-wing thought increased, and in response, as Darrell William Davis explains in Picturing Japaneseness (1996), "the political situation turned toward authoritarian imperialism by the time of the Manchurian Incident (1931)" (62).

Pro Kino

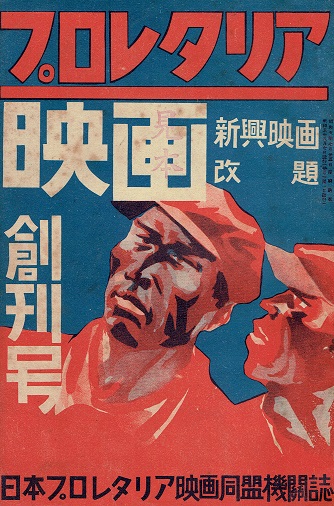

Government officials' hands were full enough in 1929 to somehow permit the formation of the Japan Proletarian Motion Picture League, nicknamed "Pro Kino" (short for proletarian cinema), which was dedicated to "mak[ing] documents of the Communist movement in Japan" such as "demonstrations, slums, and May Days" (Anderson, 69). This group operated for a whopping 4 to 5 years before being suppressed under the Peace Preservation Law. The time period was succinctly characterized by Noto Setsuo, a former member of Pro Kino, in a 1994 interview: "That's the kind of time it was. In the movement, it was a time when you'd get caught the minute you did anything" (Makino).

First Issue of Pro Kino's Publication "新興映画" (Emerging Films), 1930

Proletarian and Marxist themes will be explored further in the last section, particularly in films set in contemporary Japan.

Continued in Pt. 3

Films

Citations

Nikkatsu (Producer), & Ito, D. (Director). (1927). A diary of chuji's travels [Motion Picture]. Japan: Nikkatsu.

Citations

“A Diary of Chuji's Travels.” Filmlinc, Film Society of Lincoln Center, www.filmlinc.org/films/a-diary-of-chujis-travels/.

Anderson, Joseph L., and Donald Richie. The Japanese Film: Art and Industry. 3rd ed., Princeton University Press, 1982.

Davis, Darrell William. Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Film. Columbia University Press, 1996.

Makino, Mamoru, and A. A. Gerow. “Prokino.” YIDFF: Publications, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, www.yidff.jp/docbox/5/box5-2-e.html.

Comments

Post a Comment